The rich history of an El Paso landmark

Miguel Juarez

In 2011, the Texas Department of Transportation, or TxDOT, requested its demolition by the City of El Paso because it “determined that the Center is not eligible as a historical structure nor its use contemplated in the future.” This meant TxDOT did not see Lincoln Center as a historical site. The city echoed this view by sending its newly hired Historic Preservation Officer to conduct an analysis of the center and she concluded that “no information on anyone of prominence that had attended the school” or that she had “no information on anything of significance that happened in the building,” as well as other issues. Her statements were unfounded.

The fact is that the Lincoln Park community is a place that has tremendous historical significance, but it has been overlooked. It is situated in proximity to what was once Concordia, which was the site of the first Mexican community north of the Río Grande. In 1852, Hugh Stephenson built several buildings and his home at this site. In 1854, he built a chapel named “San José de Concordia el Alto” and the cemetery that still exists. The chapel was located at the corner of Rosa Street and Hammett Boulevard. On February 6, 1856, a deer gored and killed Juana Ascarate Stephenson and she became the first person to be buried in the Concordia Cemetery. Stephenson lost his land after the Civil War, but his son-in-law, Albert H. French, purchased the property at a federal marshal’s sale in 1867. In 1868, when the Magoffinsville Post was flooded, Fort Bliss moved to the area south of Concordia Cemetery (now the Lincoln Park community) and it became known as Camp Concordia. It operated as a military base from 1868-1876. The post was later abandoned in 1876 after the troops left El Paso before moving to Hart’s Mill from 1878-1883.

In a 1989 article written by Mary Bowling and published in Password, the Journal of the El Paso County Historical Association, in 1975, Lillian E. Scott, who had been a teacher at Lincoln School for seven years passed away and she left behind a small journal with notes about her years associated with the school. Mary Bowling had been a student at Lincoln School in 1929 when the journal was found. Bowling subsequently transcribed Scott’s notes and developed a short history of the school up to 1951.

Lincoln School, formerly known as Concordia School, was first opened as a one-room school in Camp Concordia in the Officer’s Quarters in 1868. Scott wrote in her notebook that, “it was furnished with long rough wooden tables and benches, and its pupils were children of military personnel.” In 1880, the school was expanded to a four-room adobe building that had served as a guard post between 1880 and 1990; later the school opened as a one one-room brick building on Grama Street near the Franklin Canal.

Lincoln School, formerly known as Concordia School, was first opened as a one-room school in Camp Concordia in the Officer’s Quarters in 1868. Scott wrote in her notebook that, “it was furnished with long rough wooden tables and benches, and its pupils were children of military personnel.” In 1880, the school was expanded to a four-room adobe building that had served as a guard post between 1880 and 1990; later the school opened as a one one-room brick building on Grama Street near the Franklin Canal.

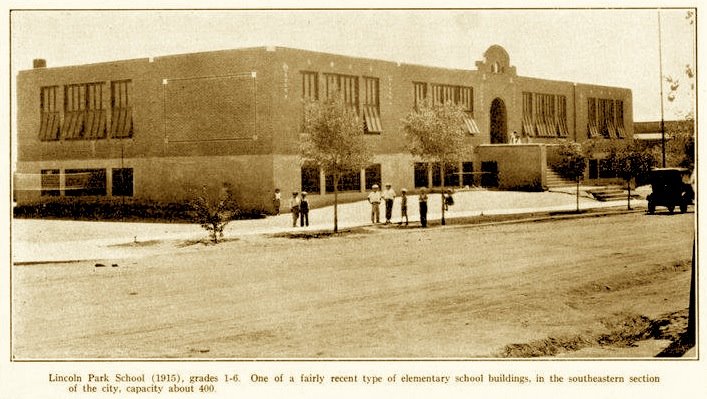

Bordered by Concordia Cemetery to the North, the Ziegler Union Stockyards to the West, Lincoln Park area was a flourishing community comprised of mostly adobe buildings from as early as the late 1800s at the edge of civilization. In 1909, when the Lincoln Park Addition was registered with the El Paso City Clerk’s office, a two-room school building was created at the present site (4001 Durazno). After the creation of the neighborhood, from 1909 to 1915, Concordia School District #2 purchased various lots where Lincoln School would later expand. In 1915, Lincoln School was expanded to a red brick building with a basement and 13 rooms.

Among the many students who attended Lincoln School, who later became prominent persons in the community, was State Representative Mauro Rosas, a former pupil of Grace Lord, who taught there for 31 years beginning in 1928. Rosas was born on December 5, 1925. He served in the US Army Air Corps and later became an El Paso Attorney. Rosas was also the first Latino State Representative from El Paso, Texas to serve in Austin during the Twentieth century in 1959 during the Fifty-Sixth and Fifty-Seven Sessions (1959-1963). Rosas was instrumental in building the El Paso Civic Center. He died September 10, 1993 and is buried at the Fort Bliss National Cemetery.

Another prominent resident who attended Lincoln School was Dr. Manuel D. Hornedo. Hornedo was born on June 11, 1903. He attended El Paso Junior College and Texas School of Mines and Metallurgy (now UT El Paso). Hornedo taught at the El Paso Technical Institute for two years before receiving his M.D. degree from the Medical Branch of the University of Texas. He later joined the United States Public Health Reserve and worked at the El Paso City-County Health Unit in 1933 as a Clinician. In 1952, Dr. Hornedo was appointed Health Officer for the City and County of El Paso and Director of the El Paso City-County Health Unit.

Another prominent resident who attended Lincoln School was Dr. Manuel D. Hornedo. Hornedo was born on June 11, 1903. He attended El Paso Junior College and Texas School of Mines and Metallurgy (now UT El Paso). Hornedo taught at the El Paso Technical Institute for two years before receiving his M.D. degree from the Medical Branch of the University of Texas. He later joined the United States Public Health Reserve and worked at the El Paso City-County Health Unit in 1933 as a Clinician. In 1952, Dr. Hornedo was appointed Health Officer for the City and County of El Paso and Director of the El Paso City-County Health Unit.

As late as 1953, Stephenson Street, named after the founder of the area, was located north of Durazno Street and East of Lincoln School. The street was removed in 1973 when the City of El Paso requested the use of the space beneath 1-10 for a public purpose–to develop open space and Lincoln Park was created. Nestor Valencia designed the park. A January 8, 1962 article in the El Paso Herald-Post signaled the arrival of Interstate 10 with the buying of land in El Paso’s East side. That same article featured a photograph that outlined the path the freeway would take from Virginia Street to Hawkins Street and through the Lincoln Park community.

In 1970, EPISD sold Lincoln School and adjoining 23 acres to the Texas Department of Transportation or TxDOT so it could be used as a field office to build Interstate 10, Gateway East and West and eleven elevated structure or overpasses on 23 acres. In October 1970, the EPISD deeded the building to the State of Texas Department of Transportation or TxDOT to be used as a staging location for the construction and maintenance of Interstate 10 and Gateway East and West. That was also the year Lincoln School was closed.

In 1970 El Calvario, a stone church that had been built in 1933, that was located at the corner of Durazno and Martínez Streets, was demolished to make way for a freeway column to hold a section of Highway 54 leading to the Bridge of the Americas Port of Entry. One of the options for Lincoln School that was considered in that period (1974) was for it to be used as a satellite campus for El Paso Community College.

According to a report by the city of El Paso, Community Development Block Grant Funds were to used to renovate Lincoln Center: $100,000 in 1976 to renovate the center; $56,898 in 1978 to install an elevator; $24,950 in 1987 to replace the roof, and $29,000 in 1988 to repair and renovate bathrooms. The Lincoln Cultural Center, at the time was the only cultural arts center run by the city, and it operated from 1977 to 2006.

From 1977 to 1987 it housed several Parks and Recreation offices; the League of Latin American Council Project Amistad offices; Project Bravo, and also featured a recreation room with pool tables, a meeting room and classroom for informal gatherings and a gallery that was used by local artists for monthly exhibits.

Latino cultural arts center

The Lincoln Arts Cultural Center was the only arts center run by the city’s Parks and Recreation Department in a predominantly Mexican-American community and it was used by the entire city, so by default, we can say that it served as the city’s first and last Latino cultural arts center. Currently, in 2012, there is no Latino Cultural Art Center in El Paso, a city where more than 80 percent of residents are Mexican and Mexican-Americans/Chicanos.

In 1983, Bobby Aduato, Lincoln Center director, asked Chicano artist Felipe Adame to paint murals on the pillars under the Spaghetti Bowl freeway interchange at Lincoln Center. Adame sought to replicate the creation of murals at Lincoln Center like murals in Chicano Park in San Diego. He had been involved in the painting of murals at Chicano Park in San Diego for many years and continues to be involved today. Adame had hoped to paint additional murals on freeway columns but due to a lack of funding he could not paint more. It would not be until 1999 when other artists would advance his idea.

In addition to the exterior murals painted on the columns at Lincoln Park, other important murals were painted inside the Lincoln Center, one titled “Tribute to Abraham Lincoln,” painted by Artist Carlos E. Florés in 1984, as well as “Amistad/Friendship,” also by Florés, painted in 1985, assisted by Fermin Montes, Manuel Guzman, Ana Ramos, Flaviano Ortíz, Fernando Galvan, Carlos Casillas, and Enrique Florés. The murals were painted with funding from the El Paso Parks and Recreation Department and the Upper Rio Grande Private Industry Council (PIC).

Florés attended La Academia de San Carlos. La Academia de San Carlos in Mexico City, the first major art academy and the first art museum in the Americas. He studied painting under Maestro Luis Nishisawa. Nishizawa is recognized as one of México’s leading landscape artists of the 20th century. This is the same university attended by Méxican artists like Saturnino Herrán, Roberto Montenegro, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco.

In 1985, the Lincoln Art Gallery presented “Juntos 1985” 1st Invitational Hispanic Art Exhibit organized by Paul H. Ramírez and myself. The exhibit featured prominent artists from El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, including the late Manuel G. Acosta, the late Rudy Montoya, the late Luis Jiménez Jr., the late Marta Amaya Arat, Ernesto P. Martínez, Mago Orona, Antonio Piña (who was a student at Lincoln School), Paul H. Ramírez, Miguel Juárez and Ciudad Juárez Artists: Noel Espinoza, Miguel Varela, Alicia Acosta De Sanz, Ildefonso Bravo, Velia Carranza, Elvira Fe de Mirano, Rebecca Antuna, Antoñio Arrellanes, Irma Camacho, and Lucina Chavéz. The Honorable El Paso County Judge Alicia R. Chacon, who was a city representative at the time, was instrumental in supporting the exhibit.

The El Paso artists in the exhibition included a who’s who in El Paso Latino Art, including the late Manuel G. Acosta, and the late Luis Jiménez who created “Los Lagartos” in San Jacinto Plaza. In 1986, the gallery was the site of the “Juntos 1986: Hispanic Photographers Exhibit” that included notable Latino photographers, including Internationally recognized photographer Carlos Fernández. This exhibit led to the creation of the National Association of Chicano Arts (NACA) that changed its name to the Juntos Art Association in 1986 (presently a Latino Arts and Cultural organization in its 25th year).

Numerous other El Paso artists and photographers have exhibited in the gallery and numerous performance groups have performed in the amphitheater next to Lincoln School. It is estimated that from 1981 to 2006, the Lincoln Art Gallery hosted about 3,000 local and school-children artists. Lincoln Center served not only the Lincoln Park Neighborhood, but also the residents of the Durazno and Chamizal Neighborhoods.

Murals, hot cars and evacuations

In 1999, Chicano Artist Carlos Callejo, who years earlier (1993-95) had been commissioned to paint a large mural titled “Our History,” in the El Paso County Courthouse at 500 East San Antonio Street in downtown El Paso, proposed and completed a mural project for Lincoln Park in conjunction with the Private Industry Council (PIC). He proposed to work with 80 students from various school districts. They also produced a video on the creation of the murals and sponsored art classes at the Lincoln Center. The project hired five artists to work with them in producing the murals. The artists included Cesar Inostroza, Fabian Arraiza, Steve Salazar and two women who were not artists but youth supervisors.

Inostroza and Callejo continued painting murals after funding for the project ended. Callejo said each row of columns were dedicated to various themes, one row was titled “Memorial Walk” and was dedicated to historical figures such as Cesar Chavez, Ruben Salazar, Martin Luther King and another row was dedicated to the “Natural Elements:” Mother Earth, Father Son, etc. Callejo organized a community group that included individuals fromthe neighborhood to approve the themes for the murals.

In 2005, the Latin Pride Car Club organized the “First Annual Lincoln Park Day” at Lincoln Park. The event was modeled after similar events held at Chicano Park in San Diego. A year earlier, in 2004, Hector González, firefighter and president of the Latin Pride Car Club, had e-mailed the City of El Paso concerning the fate of Lincoln Center. After the floods in 2006, the city had shut the center down with plans to reopen it. González’s fire unit had been called to help Saipan-Ledo residents evacuate their homes during the 2006 floods. Lincoln Center was used as a rescue station for people escaping the flooding in the Saipan-Ledo neighborhood, where 56 homes were destroyed.

In 2006, the Latin Pride Car Club organized the “Second Annual Lincoln Park Day,” following in 2007 with the “Third Lincoln Park Day,” and in 2008, the “Fourth Lincoln Park Day.” In 2008, brothers Hector and David González and Artist Gabriel Gaytán created the Lincoln Park Conservation Committee or LPCC to advocate for the needs of Lincoln Park. In 2009 and 2010, LPCC presented the Fifth and Sixth Annual Lincoln Park Days.

In 2009, a mural titled: “El Corazón de El Paso,” was painted on a 30-foot-by-20-foot T-shaped freeway column by Gabriel S. Gaytán. Gabriel’s son, Gabriel Itzai assisted Gaytán in the painting of the mural, as did the members of the Latin Pride Car Club who helped with scaffolding and materials.

The idea for the mural came from David González a member of the Latin Pride Car Club, who sponsored the mural project and commissioned it. González gave a sketch to Gaytán who then added images of the Franklin Mountains as well as the star on the mountain, and Mexican pyramids that symbolized El Paso’s over 85 percent Mexican-American heritage and population. The main image of the mural was that of a human heart with highways as arteries. Freeways US 54 and I-10 meet at Lincoln Park and spread out to other highways throughout the city.

In 2010, LPCC joined with residents and created a Neighborhood Association and became a Partners-in-Parks that made it possible to sponsor four events a year: Cesar Chavez Day in March, Lincoln Park Day in September, Día de los Muertos in November and Día/Day de La Virgen de Guadalupe in December. Proceeds generated from these events go back to offset expenses of organizing these events, for beautification of the park and the painting of murals by local area artists.

The Lincoln Cultural Center and Park remains the social anchor and meeting place for the community and meetings are often held outside of the closed center. One of the goals for LPCC has been to collaborate with city of El Paso to make Lincoln Park and Center a cultural tourist destination for the arts. In partnership with the El Paso Convention and Visitors Bureau, in early 2010, the LPCC printed 10,000 full color brochures to promote the murals and the park.

After years of trying to find out who owned Lincoln Center in a City Council meeting on October 4, 2011, El Paso City Manager Joyce Wilson stated that the city did not own Lincoln Center, that the Texas Department of Transportation or TxDOT was the rightful owner. At that same meeting, LPCC learned from Wilson that Lincoln Center was slated for demolition and that the newly renamed and remodeled O’Rourke Center (formerly the YMCA) at Virginia and Montana Streets (located four miles away) was the replacement for Lincoln Center.

Using Freedom of Information Requests (FOIAs), LPCC requested e-mails from the city that documented their intent to tear down the center. These documents revealed that city officials had been planning the demolition since 2007, but had not officially notified residents.

At a meeting Debbie Hamlyn, the Director of Quality of Life for the City of El Paso, presented a report to City Council regarding the demolition of Lincoln Center. Among her points was that the district had lost population and it no longer warranted a center. The LPCC stated that aside from low-income residents, this part of the city has a large undocumented population, and has historically been under-counted by the U.S. Census and that there were over 6,000 young people in immediate areas of Lincoln Center.

At Annual Lincoln Park Day on September 25, 2011, thousands gathered to celebrate the park and unveil a new mural by Gaytán and experience one of the largest regional classic car shows in the city. At the same time, under the threat of Lincoln Center’s threat of demolition, LPCC initiated the “Save Lincoln Park,” campaign by hosting a press conference with attendees and Lincoln residents. On that day, LPCC was also able to collect 200 letters to city council members and more than 500 signatures on a petition to Mayor Jonathan Cook. LPCC subsequently presented those letters and petitioned to city representatives and Mayor Cook directly.

Hamlyn pointed out that the building had issues with mold and asbestos due to the floods of 2006, however, several Open Records Requests (FOIAs) to the city failed to produce any evidence of asbestos. At the meeting, City Representative for District 3, Emma Acosta, introduced a resolution to grant a reprieve to Lincoln Center for six months while the city communicates with the neighborhoods surrounding Lincoln Center regarding its demolition. The resolution passed unanimously. Several LPCC members, supporters and community residents spoke on behalf of keeping Lincoln Center open and stopping its demolition.

At the first public input meeting on January 11, 2012, six years after the public facility had been closed, at the Silva Health Magnet School, city engineer, R. Alan Shubert, stated that no asbestos had ever been found in the building. This was the first time city officials admitted that they had obviously communicated inaccurate information about asbestos having been the reason to close the building.

Without a doubt, Lincoln School is the El Paso region’s first and oldest elementary school, created 14 years before the El Paso Independent School District was incorporated (EPISD was created in 1892). The proposed demolition of the building must be stopped and the City of El Paso needs to work with LPCC members and with citizens of El Paso and develop a plan to refurbish, restore and reopen Lincoln Center and not to destroy a building with so much history of our gente. Everyone needs to stand up for what is right and not just the residents of Lincoln Park.

One of the ideas generated so far have been to reopen Lincoln Center as a Latino Cultural Arts Center, but more ideas are welcomed.

Miguel Juárez is a doctoral student at the University of Texas at El Paso focusing on United States, Borderlands and Urban History, as well as a member of the Lincoln Park Conservation Committee. He can be reached at: [email protected]